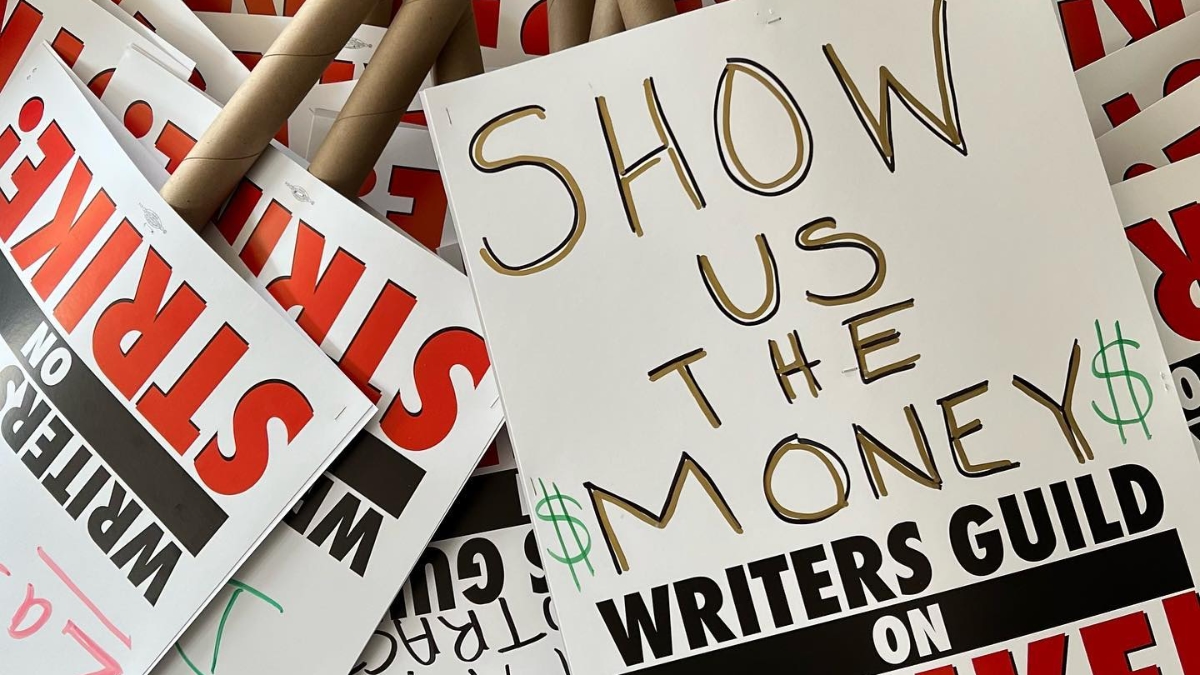

The Writers Guild of America (WGA) went on strike on Tuesday for the first time since 2007. At 1pm local time, writers began a rotating picket in front of the offices of major entertainment companies in New York City and Los Angeles in what could become a protracted campaign, but ultimately a necessary one.

The guild’s negotiators were at the table until late Monday, but the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP), which represents the major studios, broadcast networks, and streaming companies, were not willing to make nearly enough concessions for a fair deal. After it became clear that one would not be reached, the WGA said, “The companies’ behavior has created a gig economy inside a union workforce, and their immovable stance in this negotiation has betrayed a commitment to further devaluing the profession of writing.”

These negotiations are about the future of screenwriting as a profession. Figures released by the union show that median writer-producer pay on TV series is down 23% over the past decade when adjusted for inflation, while 49% of writers are getting paid the absolute minimum in their agreement, compared to 33% a decade ago. Most writers also tend to work fewer weeks per season of television as viewing has shifted to streaming and companies make far fewer episodes per season.

The WGA got some language in its contract around new media after the 2007 strike, but it hasn’t been nearly enough to protect writers from the erosion in their pay and conditions that companies have been able to get away with as the industry embraced streaming over the past decade. While major companies consolidated, it was also an opportunity to put pressure on many of the workers who make the shows and movies that fill streaming catalogs and generate massive profits.

Two years ago, it was the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees that nearly went on strike before narrowly approving a new contract, and this year the Directors Guild of America and SAG-AFTRA, which represents actors, have also signaled they face contentious negotiations as a result of how streaming has altered. Their contracts expire on June 30.

At its core, this strike is about who gets to decide how new technology is deployed and who benefits from it. The WGA is responding to how tech and entertainment companies deployed the streaming model and structured it to serve their ends, which included squeezing labor. It’s for that reason that the union is also looking forward to new technological threats coming down the line, and demanding language around the use of AI in screenwriting in the new collective agreement to protect against the possible impacts of ChatGPT and similar tools.

The sticking points

After negotiations broke down, the WGA released a two-page document comparing their demands with the offers made by the AMPTP. It very clearly demonstrates the gulf that exists between the two sides, as many of the WGA’s key proposals were rejected outright. I won’t outline every demand, but there are a few I want to focus in on as they show the divide that exists and how new technology has allowed companies to reshape conditions in their favor.

One of the big issues for writers — and many other film workers renegotiating contracts — is residuals. They’re the extra payments that go to people who worked on a film or television show for rights sales, reruns, home video releases, streaming releases, and other instances they generate additional revenue. But now that most programming gets dropped in a streaming library and doesn’t go anywhere else, residuals can be significantly less.

Part of the reason for that is the opacity on how well shows do. In the past, it was easy to get numbers on television viewership or box office ticket sales, but companies refuse to share good data for viewership on streaming services. The WGA wants to start getting that data — as do the other guilds — so they can set up a residual based on viewership, so if a show does well on streaming, the residual would be higher. But the AMPTP has rejected that proposal outright because that data is a source of power for the companies as long as it remains secret.

Another issue is mini rooms. This is a practice where studios hire fewer writers than in a traditional writers’ room that get paid less and have less input on the show. It’s particularly bad for writers trying to break into the industry, as mini rooms make it harder for them to get experience and move up. The WGA demanded commitments on minimum staff levels in writers’ rooms and minimums on the duration of their employment. But all those demands were rejected by the AMPTP.

If we’re thinking about tech, the other issue here is artificial intelligence. We’ve all seen the hype over chatbots and AI in recent months as ChatGPT has taken the world by storm and tech companies have been falling over one another to roll out new AI tools of their own. Boosters have been endlessly hyping up many of their potential applications, but given that these tools make use of large language models, there’s been a particular focus on how they could be used in writing.

Recognizing that this could be used against writers in the same way the shift to streaming has been, the WGA included demands around artificial intelligence and tweeted in March that they were designed to ensure “the Companies can’t use AI to undermine writers’ working standards including compensation, residuals, separated rights and credits.” They want to ensure that AI-generated text can’t be used as source material to be adapted by writers, or that AI tools can’t be used to generate original writing to be used on film or television projects. Ultimately, where AI is used, the WGA is demanding that full credit still be given to human writers. But once again, the AMPTP rejected that demand, and offered only to have annual meetings on new technology.

Who benefits from technology?

In an interview with the Hollywood Reporter after the talks broke down, WGA negotiating committee co-chair Chris Keyser was very clear about the position of the major entertainment companies, saying they are

taking what used to be a real career and turning it into a series of gig jobs by more or less eliminating term employment, or reducing it greatly. And what happened in these negotiations, we saw again and again, evidence of that. They would not deal with us on AI; they said, we don’t want to be restricted in using a technology that we might be able to adopt for our purposes.

Beyond the entertainment industry, we’ve been talking for years about how tech companies have been using digital technology against workers to carve them out of employment protections and throw them into the gig economy or expand the scope of algorithmic management to further empower employers. The heated negotiations between the WGA and AMPTP show that this has also affected workers in the film and television industry as companies used tech disruption to change the nature of work to increase their power at the expense of workers.

WGA members deserve our solidarity. We should see their strike as part of a broader fight against technology deployed against the interests of workers and the public to empower massive conglomerates and some of the wealthiest people in the world. Warner Discovery CEO David Zaslav was ranked the most overpaid CEO in 2021, pulling in $246.7 million. Meanwhile, many writers were struggling to pay their bills. After shelling out billions to chase the streaming boom and pulling in massive profits in recent years, the companies can afford to pay them properly.

Member discussion