Kara Swisher’s Reality Distortion Field

In “Burn Book,” the longtime tech journalist tries to rewrite her story for the post-techlash era

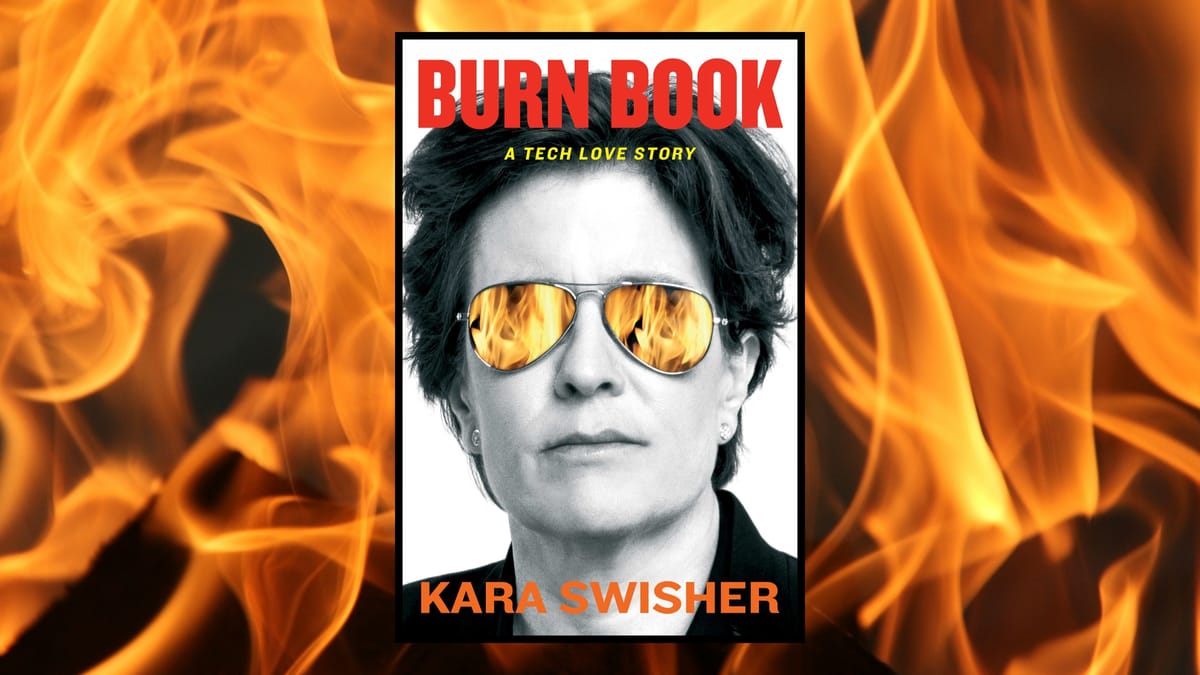

In 2004, Google was going public and cofounder Larry Page wanted users to know that pressure from shareholders wouldn’t compromise the company’s values. He wanted to write a letter explaining what the “Don’t Be Evil” motto meant to the founders, so he placed a call to tech journalist Kara Swisher to get her help, as she recounts in her new memoir Burn Book: A Tech Love Story.

It might seem odd for a tech CEO to reach out to journalist — someone whose job is presumably to hold the powerful to account, not help them with public relations — but Page had good reason to think otherwise. At the time, Swisher was married to a Google vice president and describes spending time with Page and his then girlfriend, along with many other rising figures in the tech industry. She was covering them, but she was also in their social circles and truly believed they were changing the world for the better.

“Page must have figured I was friendly or, even, a friend,” she writes, “though I was neither.” That’s hard to believe. She claims she didn’t help with the letter, but based on what she recounts in the book, it would be one of the rare times she didn’t want the feeling of importance that came with imparting some advice to a tech founder.

As I read that story, another came to mind — one that didn’t make it into the book but provides quite a contrast. In May 2014, Google’s other cofounder Sergey Brin showed up at the Code Conference that Swisher co-hosted with Walt Mossberg. Partway through the onstage interview, they rolled a clip of Swisher visiting Google HQ to ride in its prototype “self-driving” car. As it whipped Swisher around the parking lot, she was shown calling it “delightful,” “cool,” and “conceptually where things are going.”

Swisher took a dig at Google Glass — not an uncommon opinion by then — and noted some reservations about the lack of human access to things like brakes or a steering wheel, but was supportive of the project. Along with Mossberg, she gave Brin ample time to lay out his vision and repeat his talking points, pumping more hot air into the growing hype around the prospect of ubiquitous self-driving vehicles — that were, they all told us, only a few years away.

At one point, Brin even told the pair, “We have not had any crashes. We test these things very carefully.” In 2018, the New Yorker reported that was not true: the team had a bad safety culture and one of its leaders had even fled the scene of a crash after a vehicle using its self-driving system forced a Toyota Camry off the road in 2011. But Swisher helped him spread that false narrative. A decade later, self-driving cars are facing another reckoning on safety, including Google’s Waymo, and are still far from achieving widespread deployment. Yet in the final pages of the book, Swisher writes that she still “loves” autonomous vehicles and that they’re finally reaching a point of “true utility.”

A journalist can still be a founder

These stories show the tension at the heart of Swisher’s story. In Burn Book, she’s trying to position herself as the thorn in Silicon Valley’s side for the past several decades; the rare truth-teller in a sea of yes men (and women). She brags about how almost all the big names of the Valley would take her calls and text her about all manner of topics — Marc Andreessen would “always pick up the phone for me, at all hours,” she gloats — and wants readers to feel that didn’t influence her or stop her from asking the tough questions.

Yet Swisher admits she “started out as a reporter” before becoming more of “an analyst, and sometimes an advocate,” and that even after the dot-com crash, she was “still a believer.” She even crafts her own tech origin story, where she was great at math in school, showing “a whiff of early genius,” but got bored of her classes “like many in tech,” agreeing with Peter Thiel that school was “a huge waste of time.” Her plan to become an analyst for the military or Central Intelligence Agency didn’t work out because of the homophobic attitudes of the public service at the time, so she went into journalism instead.

Later, during a fellowship at Duke University while she was employed at the Washington Post, Swisher recounts her first interaction with the World Wide Web in the early 1990s. After downloading a book of Calvin & Hobbes comics, she realized “everything that can be digitized will be digitized.” Throughout the book, this revelation becomes like a gospel and anyone who doesn’t accept the inevitability of digitization is presented as backward and deserving of her scorn.

Swisher assures readers she was on board with the digital revolution from the very beginning, reportedly telling the higher ups at the Wall Street Journal that they should shut down their printing presses even while print was still generating massive profits and deriding Hollywood figures for not realizing that “resistance was futile.” She turned down plenty of opportunities to cash out, claiming she wouldn’t have lasted long enough as an employee for her shares to vest.

All of this is used to present herself as an entrepreneur who didn’t belong in the old media world, first creating All Things Digital under Dow Jones before branching out with Recode a decade later, which had a “fitting startup mentality.” It was her own founder’s journey, so to speak, and she certainly has a lot to say about founders. But for a “burn book,” it doesn’t have many juicy details most tech watchers wouldn’t already know.

Selective outrage at the “man-boys”

The Great Men (and occasional Woman) of Silicon Valley dominate the stories we’re told about the tech industry, and that’s no different in Swisher’s version of events, especially given how much she valued the relationships she had with them. She claims to have not had much time for the “man-boys” whose profiles rose in the dot-com era and ascribes many of their personas to bad relationships with their fathers, but if you were looking for damning details about today’s tech titans, you should look elsewhere.

For the tech crowd, the few figures she really subjects to extended criticism are Mark Zuckerberg, Travis Kalanick, and Elon Musk — probably some of the easiest people in tech for anyone to criticize these days. Zuckerberg and Meta have been singled out as some kind of unique evil to distract from Silicon Valley’s broader problems for years, especially since the Cambridge Analytica scandal in 2018, while Swisher’s vendetta against Musk is much more personal and only goes back to him calling her an “asshole” after he bought Twitter. Before that, they were on good terms and Swisher would regularly heap praise on him and his pursuits.

What stood out most to me was what she said about Kalanick, the former Uber CEO, because it shows the reality distortion field Swisher has created for herself. In the book, Swisher says that Kalanick’s rise made her “sick to my stomach.” She makes explicit reference to an interview she did with Kalanick at that same Code Conference where she boosted Google’s self-driving car — something she continued doing in the interview with Kalanick — and writes about her shock that Kalanick admitted he wanted to roll out autonomous driving not to make people safer, but to make himself richer by replacing human drivers. He represented “the ever-uglier face of tech,” she writes. Based on that description, a reader might expect that Swisher really nailed him in the interview, but that’s not the case.

If you go back and watch it, you’ll see Swisher tossing her usual softball questions, and even saying Kalanick is “not as much of a jerk as I thought he was.” As he tears into taxi companies and calls them “evil,” Swisher says it’s “fascinating” that people hate Uber when taxis also have driver issues. When Kalanick starts talking about replacing drivers with software, Swisher doesn’t push back as her book might suggest, but actually quips, “people are such a pain in the neck.” In a Vanity Fair profile she wrote later that year, she only mentions Kalanick’s apparently egregious comment in passing and wraps up the following assessment: “For all his rough edges, Kalanick's commitment to his company is almost tender at times.”

This is typical of Swisher, casting herself as a tough interviewer today when she rarely spoke out against the powerful people in the industry she covered when it really mattered. Near the end of the book, she spends a whole chapter listing people in tech she thinks are great, and among them is Brian Chesky, the cofounder of Airbnb who’s helped exacerbate housing crises around the world and who should be right alongside Kalanick, but hasn’t had the same public fall from grace. Similarly, she spends the better part of two chapters gushing about Steve Jobs, and little more than a sentence acknowledging that he actually did a whole lot of terrible things as a business leader.

Swisher’s focus is almost exclusively on the C-suite. While she spends some time detailing the mistreatment of women in white-collar jobs at tech companies, the general abuse of workers within the tech industry and, more broadly, how companies have used technology to deskill and disempower workers throughout the wider economy is largely absent. She was happy to praise Musk even as his workers were slaving away in a factory they dubbed “the plantation,” subject to high injury rates, and Musk was going “demon mode” on them, as biographer Walter Isaacson described, because he was building a future of electric cars and rocket ships. She acknowledges her opinion of him only really changed when he became “Twitter Elon”; “Tesla Elon” and “SpaceX Elon” were just fine, even though the stories of his terrible management go right back to Zip2.

If he hadn’t called her an asshole and started tweeting out homophobic and anti-semitic conspiracy theories, he’d still be in her good books today, just as Steve Jobs is even though he had a terrible labor track record himself: from getting sub-contracted immigrant workers in basements across Silicon Valley to make Apple’s boards in the early days to dismissing the suicides at Foxconn’s Chinese factories decades later. Labor is expendable to Swisher, as long as the CEOs present themselves well enough. She openly admits as much: as long as they have a good “prick to productivity ratio,” she’s willing to give “flawed people … a little break” — but they have to return her calls.

The story doesn’t add up

A supposed “burn book” that tries to present its author as a truth teller can’t be without some criticism of the tech industry, but what Swisher provides is stale and even contradictory. In her telling, the problem with the tech industry is boiled down to the misinformation spreading on social media and the isolation caused by our addictive devices. Zuckerberg is pilloried for his responsibility for the former, even as other social media CEOs like Snapchat’s Evan Spiegel come in for praise, yet Jobs escapes any responsibility for the iPhone and iPad’s contribution to the latter.

In the final chapter of the book, Swisher has to admit that the digitization of everything she championed has been “disastrous,” but seems unable to comprehend the sheer scale of that disaster. The promises of the supposed digital revolution have often failed to be realized, while the drawbacks we weren’t informed about just keep escalating. Tech’s calls for disruption were the justification for an assault on labor rights by companies like Uber and Amazon, while the financialized nature of the business distorted industries far beyond computer hardware and software as public companies and startups alike chased “tech” valuations by shoving digital tech where it didn’t belong. Now our appliances are stuffed with useless tech that make them not last as long and our cars are equipped with big touchscreens that make driving less safe if you try to change the temperature or adjust the volume while cruising down the highway.

Her solutions to the problems in tech are little more than vague calls for regulation and more diversity to combat the “white male homogeneity,” ignoring that when women and people of color reach executive positions they have a tendency to act largely the same as the men. Think of Arianna Huffington’s attempt to protect Kalanick as the scandals escalated, Elizabeth Holmes’ massive fraud that harmed real people, or Sheryl Sandberg’s career defending Facebook’s actions. The problems exist on a deeper, more foundational level that is inconceivable to someone who champions the tech industry as, ultimately, a force for good.

The world Silicon Valley created is a disaster, and journalists like Kara Swisher had a responsibility to look beyond the bold visions and public relations theater to tell the public what we were really being sold. But on far too many occasions she echoed what her powerful contacts told her in the calls they’d always answer — and she knew the role she played. She recounts how in 2017 she asked Musk for a short video to celebrate Mossberg’s retirement but he refused and eventually told her to stop emailing him. Musk was “biting the hand that fed him,” she writes, noting how important media coverage was to boosting his profile, but never acknowledging that was why he cultivated a relationship with her and so many other journalists in the first place. He was reaching the point where his position and wealth meant keeping them on side was far less necessary.

Tech journalism failed the public

In the end, Burn Book is the story of one of Silicon Valley’s most prominent access journalists who took a page from the billionaires she covered and created her own narrative to see and present herself as something else entirely. The story Swisher is trying to tell helps to distance herself from the decades she spent boosting companies that have now been “disastrous,” as she herself admits, but it also works for the industry. Letting Swisher present herself as a tough reporter allows Silicon Valley to pretend it was being held to account this whole time — when really Swisher was along for the ride and bought into the tech determinist worldview guiding the industry.

Swisher is a great example of what went wrong in tech reporting through Silicon Valley’s long boom, from the starting gun of internet privatization to the post-Trump techlash. Journalists like Swisher got far too close to the people they covered and bought into the lies they were weaving as the money rushed in and everyone got rich. They got too absorbed in the deceptive story the industry told itself to question whether it all made sense, even as they helped sell the narrative of tech’s promise and inevitability to the public. Now we’re all dealing with the fallout of that period, and while some have admitted they got it wrong, far too many are trying to pretend they were asking the hard questions the whole time.

Swisher spends her last chapter repeating much of the bullshit about generative AI that tech executives have been spreading for the past year, calling it a new “Cambrian explosion,” musing about the ways it could improve virtually every aspect of life, and complimenting Musk for conflating human and computer intelligence a few years back. It shows just how little she’s able to cast a critical eye on what she covers, and how influenced her opinions are by the tech power players she turns to for assessments of the industry. Swisher closes the book by pasting in some nonsense generated by ChatGPT and repeating claims about driverless cars and workplace automation that feel a decade out of date. After all this time, she still can’t see through the hype when it actually matters.